by Mike Males

The latest manifestation of White Americans’ open racial animosity, from the election of President Donald Trump to the recent violence in Charlottesville and the emboldened rhetoric of White nationalists since then, suggests continued anxiety that research indicates is grounded in an overriding fear of non-Whites.

But new data show that fear is irrational.

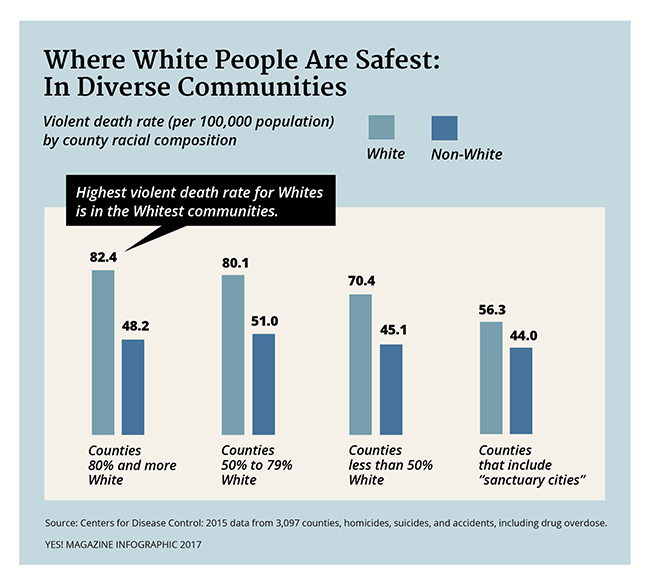

While White people tend to feel safer when they dominate the population, and feel threatened by the visible presence of other races, they actually are safer in racially diverse communities.

Trump’s voters—nearly 90 percent of whom are White and average$72,000 in median family income—were often motivated by anxiety over increasing diversity and “racial resentment,” especially toward “illegal” immigrants. Trump stoked his constituents’ fears associating immigrants with violence and drugs, claiming they kill “innocent American(s)” abetted by liberal, immigrant-friendly sanctuary cities that “breed crime.”

Trump’s demagoguery resonates because it comes amid one of the most dramatic public health declines on record: the fall in recent decades of middle-aged Whites’ from America’s safest demographic to its most endangered today. From 1990 to 2015, deaths of Whites 40-64 from drug overdoses rose from 3,000 to 22,000, suicides rose from 9,000 to 19,000, and total violent deaths rose from 24,000 to 58,000.

According to Princeton University economist Angus Deaton, there is correlative evidence that Donald Trump is doing very well in the same areas that are hardest hit by this decline. “…I think it is pretty clear that Mr. Trump has locked into this group of people who are feeling a lot of distress one way or another,” Deaton said in an interview with Politico.

They are stressing, overdosing, and dying violently at rates surpassing less-advantaged non-White, younger, and poorer cohorts. And their worst death trends and levels are in predominantly White communities.

Centers for Disease Control mortality data show that Whites are actually safer in racially diverse areas—not only from violent deaths in general but specifically from guns, drugs, and suicides.

There’s irony in many Americans’ long association of danger with mean downtown streets, and their association of safety with leafy suburban cul-de-sacs and rural lanes.

Consider the city Trump and others often identify with rampant violence: Chicago. It is true that African Americans and Latinos have high homicide rates in the city and surrounding Cook County. However, Whites there are much safer, with homicide rates less than half the national average.

The same is especially true of Whites in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Seattle, Columbus, and other large “sanctuary cities,” where local policies seek to shield immigrants from federal persecution. Whites living in and around diverse sanctuary cities are substantially less likely to die from violent death than anywhere else.

Fear-based White flight from “dangerous” cities to the “safety” of suburbs and small towns—as their urban cores and schools became more racially diverse—actually increased the odds that Whites who fled would die violently.

Conservative politics of White-dominated areas seems to play a role.

A 2016 study found Whites “living in racially isolated communities with worse health outcomes” is “one of the strongest predictors of Trump support.” Isolation reinforces the sense of white grievance and siege mentality connected to high levels of racial anxiety many Trump voters seem to feel.

Deaton refers to this wave of grievance and anxiety as “White rage.” It manifests in various reactions, he says, from support for far-right political candidates to “deaths of despair.”

As middle-aged Whites, stressed by socio-economic challenges, were most in need of health care such as mental health counseling, domestic violence and addiction services, budget cuts fueled by conservatives’ anti-tax, anti-government politics were slashing these programs. These cuts not only eliminated vital services in predominantly White rural conservative places, they muted local alarms of just how serious White distress was becoming.

Conversely, the more progressive voting patterns of racially diverse, mostly urban residents sustained many vital services that may have helped mitigate the opiate and suicide epidemics in places like New York City and coastal California. Those Whites more comfortable among diverse populations also may be less vulnerable to stresses over changing racial demographics. In New York City and urban California, for example, Whites have had more time to adjust to their growing minority status.

And there’s this. The White-safety-in-White-numbers myth can be seen as emanating from a narrative of racial superiority: Whites are safer around other Whites than around people of color because Whites are better people.

Facts to the contrary may not change self-flattering prejudices. But, over time, mundane pocketbook issues might. A New York Federal Reserve Bank analysis shows the most robust economic futures lie in “areas that are less residentially segregated by race or income,” favoring higher-quality schools and community cohesion.

Of course, continued analysis of the new violent deaths data is required. But, during this time of confronting Whites’ fears, it helps to understand that moving toward communities of diversity, integration, and multicultural environments—and the progressive social policies that often accompany them—may benefit Whites in terms of both actual physical safety and economic well-being.

—