The Carrier company’s announcement that, after exhortations from Donald Trump, it was going to move a thousand jobs overseas—rather than the 2,000 that it had previously planned to move—led New York Times reporter Nelson Schwartz (11/29/16) to declare that “Mr. Trump is a different kind of Republican, willing to take on big business, at least in individual cases”:

Just as only a confirmed anti-Communist like Richard Nixon could go to China, so only a businessman like Mr. Trump could take on corporate America without being called a Bernie Sanders–style socialist. If Barack Obama had tried the same maneuver, he’d probably have drawn criticism for intervening in the free market.

The story went on to say that Trump and Vice President–elect Mike Pence had promised Carrier they would be “friendlier to businesses by easing regulations and overhauling the corporate tax code.” Probably more to the point from Carrier’s point of view, Schwartz noted that the state of Indiana, where Pence is still governor, “also plans to give economic incentives to Carrier as part of the deal to stay.”

So Trump’s job program involves cutting business taxes and regulations, plus a corporate-welfare package whose cost will presumably be declared after media attention wanders. This makes Trump “a different kind of Republican” how, exactly?

If you’re looking for a way to protect factory jobs that doesn’t involve making wealthy corporations even wealthier, you’re out of luck. The Times‘ “other side” takes the form of liberal economists saying that there’s really no way to save workers:

- “No one should confuse what Trump is doing here with sustainable economic policy,” says Obama adviser Jared Bernstein, who isn’t quoted on what a sustainable economic policy would look like.

- “Wall Street is breathing down companies’ necks to cut costs, and the labor savings in Mexico is too great,” says Robert Reich, Bill Clinton’s Labor secretary.

- “It doesn’t address the loss of manufacturing jobs to technological change, which will continue,” declares Indiana University business professor Mohan Tatikonda.

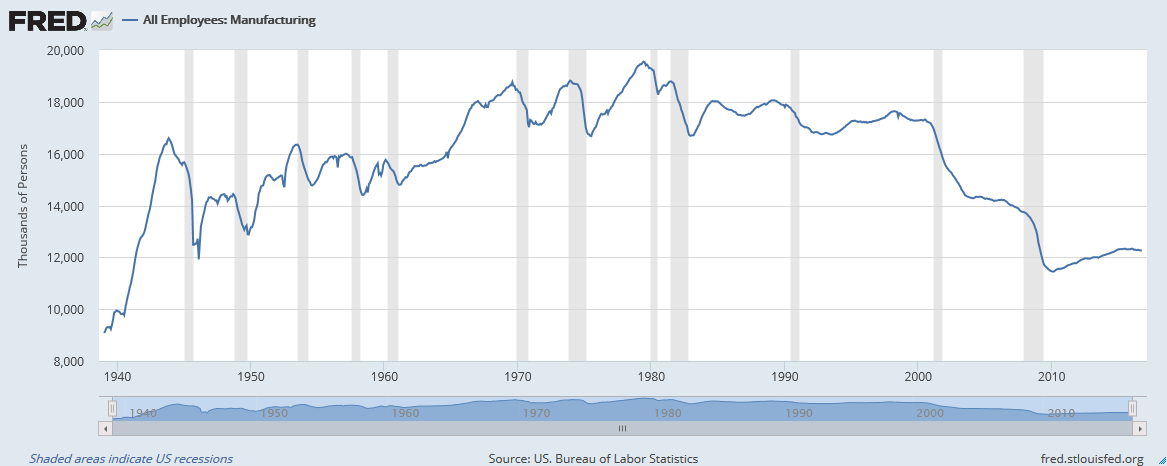

One might note that there was tremendous technological change from 1939 until 1979, when US manufacturing jobs grew from 9 million to 19 million. And there was a great deal of change over the next 20 years, when manufacturing employment held more or less steady around 17 million. Whatever caused factory jobs to plunge thereafter—from 17 million in 2000 to 11 million in 2010—it wasn’t that American business had suddenly discovered technology.

One might also note that the relative cost of labor in two countries is based on the value of the countries’ currencies; there’s always an exchange rate that would allow imports and exports to balance out. If the US has a $49 billion trade deficit with Mexico, as it did in 2015, that means the dollar is overvalued compared to the peso. It’s not a fact of nature that it’s cheaper to do business in Mexico.

But the debate in this article provides a microcosm of the media debate over jobs in the 2016 election season: On the one hand, sweeping promises to bring jobs back based on pandering to corporations, and on the other hand, fatalistic assurances that there’s no way to bring jobs back. Is there any wonder which side of this debate won the election?

Jim Naureckas is the editor of FAIR.org. You can follow him on Twitter at @JNaureckas.

You can send a message to the New York Times at [email protected], or write to public editor Liz Spayd at [email protected] (Twitter:@NYTimesor @SpaydL). Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective.